Against Strategy

Content warning: startup advice; mention of business plans; implication that I know better than other people.

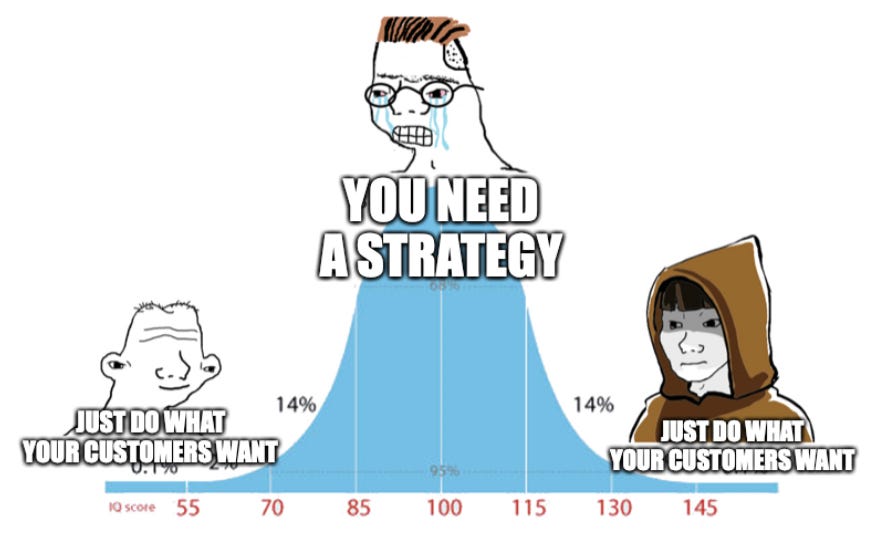

I’ve seen many startup founders led astray by the errant belief that they need more strategy.

For early-stage companies, strategy is vastly overrated. In fact, early on, too much strategic thinking is usually a negative signal. I’ve seen many more companies killed or maimed by a strategy overdose than I have by insufficient strategy.

Defining strategy

“Strategy” is one of those wiggle words that’s hard to define clearly. Take an expansive enough view and pretty much anything can be considered a strategy. (“Our strategy is to sell products to customers!”)

For the purposes of this piece, I’m using a narrower definition of strategy. I can’t define it precisely, but, as with pornogaphy, you know it when you see it. Warning signs include:

Designing a multi-step process, each step of which has to go right for the whole thing to work

Thinking about your company in the same way someone writing a Harvard Business Review case study might

Anything involving diagrams

Justifying a decision with anything other than “it’s what our customers want”

Your customers aren’t interested in your strategy

Your customers don’t care if you have a strategy. They don’t care about your master plan, your flywheel, or the way your current market is a wedge into another one. They just want you to make something they like.

That doesn’t mean you can’t think about those other things at all, but they should be distinctly secondary concerns, and you should remain on the lookout for the moments when your “strategic” thinking might be taking you further away from just doing what your customers want.

Your strategy is a series of untested assumptions

Strategy makes sense at later-stage companies because they operate at a scale and pace that makes experimentation difficult and costly. They also have a deeper track record that makes the results of their actions at least slightly more predictable.

For example, in 2018, Microsoft (belatedly) recognized that the rise of mobile and the cloud had made it impossible for them to succeed by assuming that all their core customers would be running Windows, and reoriented the entire company around supporting Macs, iPhones, Android devices, and even web browsers as first-class citizens. To make this happen, they had to reorganize the entire company, convince a bunch of executives to “step down to spend more time with their families,” and repeatedly communicate their new strategy both internally and externally—all to get 200,000 employees to fundamentally reassess how they conceptualized the business. They had no choice but to lay out a complex, multi-year strategy, because there would have been no way to steer a giant barge like Microsoft without such a plan.

Early-stage companies are so different from Microsoft in 2018 that it’s almost misleading that we use the same word for both of them. When you’re a young company, almost everything you try will fail, so any multi-step strategy exponentializes your already-high chances of failure into a near certainty. You’re also in a position where experimenting is cheap and easy, so you should err on the side of experimenting over planning. The best way to avoid having an incorrect or incoherent strategy is often not to have a strategy at all.

Strategy is an emergent property

Before he was a curmudgeonly NIMBY who thinks it’s “time to build” anywhere except in his exclusive suburb, Marc Andreesen famously claimed that rather than the popular image of a startup building a product for a specific market, what actually happens is something more like the market pulling the product out of the startup.

In other words, in a sufficiently viable market—and with sufficiently attentive founders—customer demands will shape the product into its inevitable form, no matter what the founders originally intended. Through this lens, creating something new is less a process of invention that it is one of discovery. Like archaeologists of the mind, the founders dig into their customers’ conscious and subconscious needs to uncover the hypothetical product within.

If you do this repeatedly, you will eventually end up with something that, in hindsight, looks a lot like a strategy—but it almost certainly won’t be the same strategy you would have chosen if you’d tried to plan the whole thing up front. Like a frog hopping from one lilypad to the next, you’ll eventually get all the way across the river, even if at the moment of each hop, you can only see ahead to one lilypad at a time.

Strategy becomes relevant much later than you think it does

Most founders, I think, understand this idea intuitively in the very early days. You rarely see anyone worrying too much about strategy when they’re building the first version of their product or trying to get their first customer, as doing so would be self-evidently ridiculous. The problem usually emerges a bit later down the line. You get some customers, raise some money, hire a few people, and all of a sudden start to feel like you’re a real business. And real businesses, you assume, have strategies.

Strategizing is seductive because it feels important. You’re not down there in the muck with your annoying customers—you’re thinking big picture and outlining grand visions of the future. You probably read blogs like Stratechery that analyze the strategies of mature tech companies; now you get to apply that kind of thinking to what you’re doing. Unlike the often rote, incremental work of making marginal improvements to your product or marketing, strategy feels like the kind of thing you have to be smart to do. Plus, a lot of the time, it’s just plain fun.

But giving in to the siren song of “strategy” is usually a mistake. The point at which you actually need strategy is way, way farther out than you think. I’ve personally never worked at a company that I didn’t think would have benefitted from forgetting about strategy and just trying to solve the next incremental customer need.

In which I explain why this advice applies to more than just startups, thereby delivering the payoff for the small percentage of non-startupy readers who have made it this far

An ongoing theme of this newsletter—one that I, fittingly, did not plan up front—is that long-term planning is overrated. I wrote about it in Don’t Take Notes, where I argued that an elaborate note-taking system won’t make you smarter or a better writer. And I wrote about it in The Best Career Plan Is No Plan, which is basically this essay, but for your life, with yourself as the “customer” whose needs you’re gradually discovering.

This same advice applies to the writing process itself. Sure, it usually helps to start out with some idea of where you want to go, but for most people, seeing where the process takes you is going to be more effective than doing any kind of grand strategizing in advance. The metaphor holds even more strongly for fiction, where, if you create vivid enough characters, they eventually start to “tell” you what they want. It’s kind of like doing customer discovery with imaginary people you made up.

Strategy is like wasabi, the harmonica, or when Steve Buscemi shows up in Adam Sandler movies: a little goes a long way.