How to Lose a Mind in Ten Days

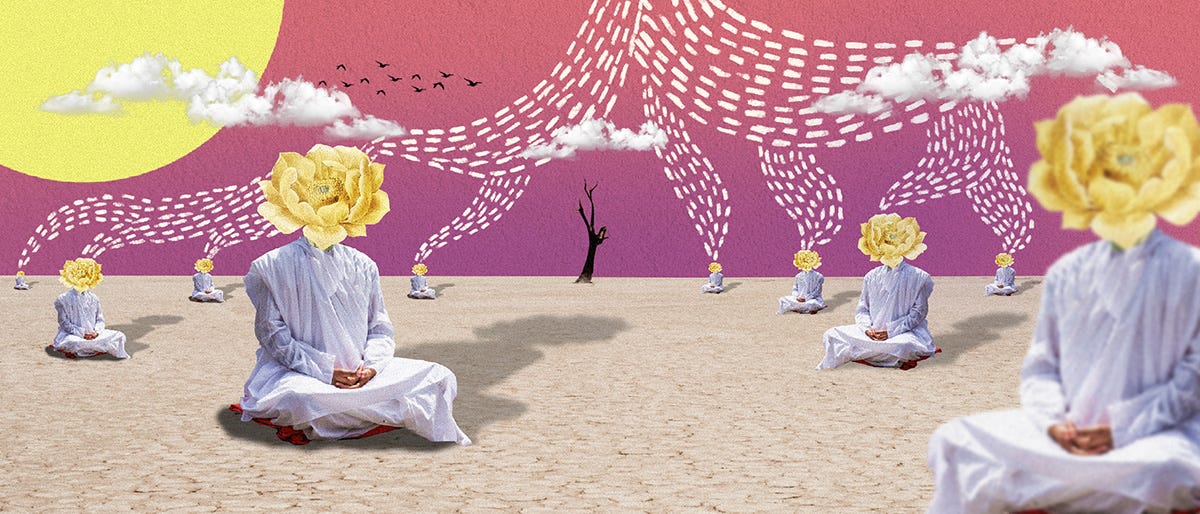

Flatulence, masturbation, and enlightenment on my silent meditation retreat

Like having a threesome, attending a silent meditation retreat is one of those subjects that it’s almost impossible to write about without seeming as though your only motivation is to brag. In fact there’s something almost perversely ironic about having an experience that’s so emphatically internal and individual, whose entire purpose is the lessening or elimination of ego, and then coming back and loudly announcing it to the whole world. Still, I did, in fact, attend a ten-day silent meditation retreat back in January. And I am, in fact, now going to tell you all about it.

The retreat I attended was one of the many run at the California Vipassana Center by famed meditation teacher S. N. Goenka—who you’ll be hearing a lot more about a bit later in this piece—and known colloquially as a “Goenka retreat.” Goenka retreats are one of the most popular for beginners, largely, I believe, due to their being the first Google result for “silent meditation retreat.” They are also free (though donations are accepted after the course), which probably helps; I have a hard time imagining how many people could be convinced to pay for ten days in what is more or less a very chill prison.

I am honestly not 100% sure why I decided to go on one of these retreats in the first place, other than that I had been meditating for five years by that point and have always been drawn to doing things in excess, even meditation. I signed up on a whim, committing in what at the time seemed like the distant future, in much the same way you might agree to lunch plans next month with someone you don’t particularly like and would never agree to meet right now.

As the retreat approached, I considered backing out several times, but by then I’d told so many people that I was going that I resolved to endure almost any torment rather than face the humiliation of publicly backing out. And so there I was, driving my rented Volkswagen Beetle from SFO to the charmingly-named North Fork, California, to sit in silence for ten days.

You get to keep your hair at these retreats, but other than that you pretty much live like a monk: for ten days, you wake up at 4am, don’t communicate with the other students—which includes not just speaking and writing but also nods and eye contact—and fast after an 11am lunch. (First-time students are allowed a fruit and tea break in the afternoon, and boy did I see some attendees milk this loophole for everything it was worth, building mile-high piles of fruit salad as if they were auditioning for a job at Edible Arrangements.)

Oh, and you also meditate for ten hours a day.

When I talk about this course with people who, like my mother, don’t meditate and think that anyone who would do something like this is insane, I often find there’s a lot of confusion about what meditation actually is. “Are you just sitting there?” is a common question.

But you’re hardly just sitting there. Meditation—especially vipassana, the type I practice—involves intense, concentrated focus on bodily sensations (starting with your breath, then “graduating” to following the slightest sensations throughout your body), as well as sitting completely still for up to three hours at a time—no scratching itches or shifting to alleviate cramps. The ten daily hours of meditation end up being so effortful that the few hours each day where you actually do get to “just sit there” become welcome respites. I’ve never craved mere boredom so much.

During my time at the center I was also told to follow five additional precepts, which I assume derive in some form from Buddhist teaching, but whose precise origins were never quite clear:

To abstain from killing any being (easy, though I did have to remind myself not to squish bugs)

To abstain from stealing (easy even for a kleptomaniac, as there is almost nothing around to steal)

To abstain from telling lies (easy, since you can’t speak)

To abstain from all intoxicants (easy, since you presumably didn’t bring any)

To abstain from all sexual activity (easy… in theory?)

A precise definition of “sexual activity” was never provided, but I had to assume it included masturbation. I didn’t ask, though, even though you were allowed to break your silence to ask a brief question of the assistant teacher. There’s not really any way to ask your meditation teacher about the regulatory status of masturbation without the question coming across as more than purely hypothetical.

And speaking of bodily functions: a brief note on flatulence. Feed 100 people a diet of mostly beans and place them in a silent meditation hall for hours on end and the result will be a symphony of poots and gurgles unlike anything you’ve ever experienced. It was as if our bodies knew we weren’t allowed to speak with our mouths and were compensating by generating sounds from as many other areas as possible. If the goal of the retreat was to get me comfortable with Zen paradoxes, they succeeded: I’ve never eaten less and farted more.

During the first few days of the retreat, I was absolutely groovin’. In the weeks before, I’d worked myself into such a frenzied lather anticipating all kinds of mental and physical horrors that I was delighted when each day turned out to be… actually quite easy. Sure, like most meditators I never fully won my daily battles with distraction, but I could feel my technique improving with each hour of practice, and I certainly wasn’t suffering from the experience—at least, not any more than some level of suffering is the baseline state of all of existence.

Besides, the California sun was on full display each day, and the retreat center was beautiful, albeit a little shabby. Really, this whole thing was kind of like a vacation. A weird vacation, where you couldn’t talk and didn’t do anything fun, but a vacation nonetheless.

Near the close of day four, after I’d fought my way through distraction and thigh cramps to meditate for three hours straight, without moving even the slightest bit—and discrediting everyone who ever called me fidgety in the process—I was filled with a euphoria that was absolutely worth four days of silence to achieve. “I nailed it,” I thought to myself, very un-Buddhist-ly. “I’m fucking great at meditating.”

Beyond sleeping, the afternoon break, and the occasional meal, our main respite from meditating was the evening lecture. Every evening, Goenka—a soft-spoken man in his mid-seventies who looked a bit like a Burmese Philip Baker Hall—would speak for around an hour, seemingly extemporaneously, on various meditation topics. Goenka teaches Buddhism more as a philosophy or set of practical systems than as a religion: his take is that Buddha was just a guy who (re)discovered an impactful meditation technique, and who would not be thrilled if he ever rose from the dead to discover that an entire religion had sprung up around his image.

But there’s a twist to these talks: like Bruce Willis in The Sixth Sense, Goenka has been dead this whole time. (More specifically, since 2013.) He “teaches” the course via video and audio recordings that were made in 1991, with two (living) assistant teachers present to guide you, and to answer the occasional question.

This is objectively insane, but even the most outrageous insanity can be made to seem normal in a high-control environment. Besides, the course’s path is so rigidly prescribed that even thirty-year-old recordings can still be strikingly relevant. When video-Goenka said, “You’re probably wondering about…,” it was almost always something I was, in fact, wondering about. He began to remind me of Hari Seldon, the prophet from Isaac Asimov’s (hugely overrated) Foundation series, emerging periodically from beyond the grave to make uncannily accurate pronouncements.

Perhaps I’m making this sound a bit like a cult. I can’t deny that it’s at least a bit of a cult of personality, given that I spent ten-plus hours watching VHS tapes of the deceased founder. But the thing about cults of personality is that they tend to emerge around people who have really compelling personalities. Goenka is engaging, funny, and impossible not to love. (If you’re curious, you can find some videos of him on YouTube, though in the absence of the rest of the retreat structure I’m not sure the effect will be the same.)

For all its oddities, the entire course has an undeniably positive aura around it. It’s free, staffed entirely on a volunteer basis, and clearly created and run by people whose own lives have been so impacted by meditation that they can’t help but share what they’ve experienced. In a way it reminded me of Alcoholics Anonymous: here is something that works for us, they were all saying, and now we would like to share it with you.

Reader, I confess that I did not make it more than halfway through the retreat without violating one of the five precepts. I’m not going to tell you exactly which one it was, but let’s just say it was violated quickly, efficiently, and with an intense focus on bodily sensations, although probably not the kind the Buddha had in mind. On the positive side, if I’m ever faced with a choice between a vow of silence and a vow of celibacy, I now know definitively which one I’ll have more trouble with.

And then it was day eight, and all at once things weren’t so easy.

Meditations that had previously felt near-effortless had become agonizing without my even noticing, and I found myself constantly fighting the urge to check my watch to see how much longer I had before each session was over. (Once, meditating in my room for what I was sure had been at least an hour, I broke my silence with an accidental shout of “Oh, fuck!” after looking at the clock and realizing it had only been about fifteen minutes.) Each bout of meditative purgatory contributed to a cycle of self-recrimination: the more I dreaded each session, the harder it was; the harder it was, the more I dreaded the next one.

And on top of that, the thought loops were really starting to get to me. More than anything else, a retreat like this teaches you how little control you have over your own thoughts. I found myself repeating the same few internal monologues over and over, well past the point where there was any further benefit to be gained by continuing to consider them. I’d catch myself thinking one of the thoughts that I knew was going to send me down the same mental journey I’d been on fifteen times before, but once that first thought broke through the surface, the rest were out of my control, and I’d have no choice but to tell myself to buckle up as I was swept along for the ride, a passenger to my own mind. Some of these loops were harmless (like the hours I spent desperately trying to remember the name of the Vincent Adultman character from BoJack Horseman), but others were much more personal, and much more painful.

When the retreat ended on the morning of the eleventh day, I sped through my assigned cleanup chores so quickly that I could tell I looked absolutely manic to the other participants. Back in my rental car, the center shrinking behind me in the rear-view mirror, I pounded the steering wheel and laughed and laughed and laughed, and I found myself thinking of Jesse Pinkman in the last episode of Breaking Bad, when he breaks out of that pit in the ground those white supremacists have been keeping him in and speeds away in that sweet El Camino.

But it took less than an hour of sitting in the cacophony of SFO before I started to miss the stillness and clarity I’d found at the retreat, and before I even got on the plane to fly home, I knew I would someday go back.

There’s this one moment from the trip I keep returning to over and over. On my last evening there the sky burst into one of those sunsets that looks like an oil painting, everything splayed out luminescent and pink, and I found a high perch by the pagoda and sat with some other students to watch until it got dark. I felt peaceful and still, and I thought about how the voices in my head were quieter than they’d ever been before, and about how maybe it took an experience this extreme to strip away all the noise and truly sit with yourself, to even realize how much of what normally goes on in your mind is noise in the first place.

And I thought about the people in my life, those I’ve loved and those I’ve hurt, those who aren’t in my life anymore and those who are so much in my life that it can feel like they’re living in my head, and I thought about how we are all of us just temporary assemblies of particles, spinning lost and helpless through this tumbling world, and for a moment I was sure I was grasping at something true and raw and real, that this, this was it, this was what I had come here to understand, and that it had all of it been worth it, every second of it, for this moment.

And then the guy next to me farted.

Yours in hoping this didn’t go on too long,

Max