In the mid-2000’s, when I was a teenager, it sometimes seemed like the entire internet had been created for just two purposes: accessing pornography and debating the existence of god.

This was the heyday of the so-called “New Atheism”—think Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris—and back then, religious flame wars were so pervasive that it was common for forums totally unrelated to religion to have a dedicated section for such discussions, just to prevent them from overwhelming the rest of the site. (Writing that sentence made me feel incredibly old.)

I was never strident about my pornography viewing, but I was certainly strident about my atheism. Not that it’d taken a Sam Harris book, or even a poorly-spelled internet post, to get me over to that side. I grew up in a secular household without much god talk, and unless you count my childhood devotion to the tooth fairy, I can’t recall ever having so much as a flicker of belief. Even the rabbi at the temple where we made the occasional perfunctory appearance said we didn’t have to believe in god, though I always suspected he was just trying to lure us in by pretending to be more laid-back than he actually was, much like one might do on a first date.

Being an atheist felt important back then, and not just because everything you believe feels important when you’re fifteen. This was the peak of the George W. Bush era, and it really did seem like religious nuts were controlling the country, and that if we could just convince a critical mass of people to be less religious, all of our political problems would be instantly solved. (Of course, like basically everything I thought when I was a teenager, that turned out to be wildly off-base—who knew that the post-religious right would be even worse?)

I never went looking for god, but I certainly went looking for something. Like many young people who want to convince themselves that their misbehavior is meaningful, I became a bit of a seeker. I was certain there was something more out there, and I was desperate to find it, even if I couldn’t explain exactly what it was. I figured I’d know it when I saw it, but either I saw it and I didn’t know it, or I just never even saw it in the first place.

I tried meditation and psychedelics and all-consuming ambition; I tried concerts and sexual experimentation and really long walks. But it never even occurred to me to try religion, and if someone had suggested it, I’d have laughed at them as hard as Sarah laughed at God when he said she’d bear a child at ninety years old—a reference I wouldn’t have gotten at the time.

I may not have found whatever it was I was looking for during this phase of my life, but along the way I had many experiences I’d describe as mystical or even spiritual. I stared at my arm in the grass until the boundaries between them dissolved and all I saw was atoms next to atoms. I lost myself in laughter at things that wouldn’t make any sense the next day—that barely even made any sense in the moment—sure somehow that the meaninglessness was the point.

But all of these experiences seemed compatible with an uncompromisingly materialist worldview, and none of them gave me a sense of the divine. I took it as a given that I would stay an atheist forever.

I lost my atheism the same way Hemingway said you go bankrupt: gradually, then suddenly.

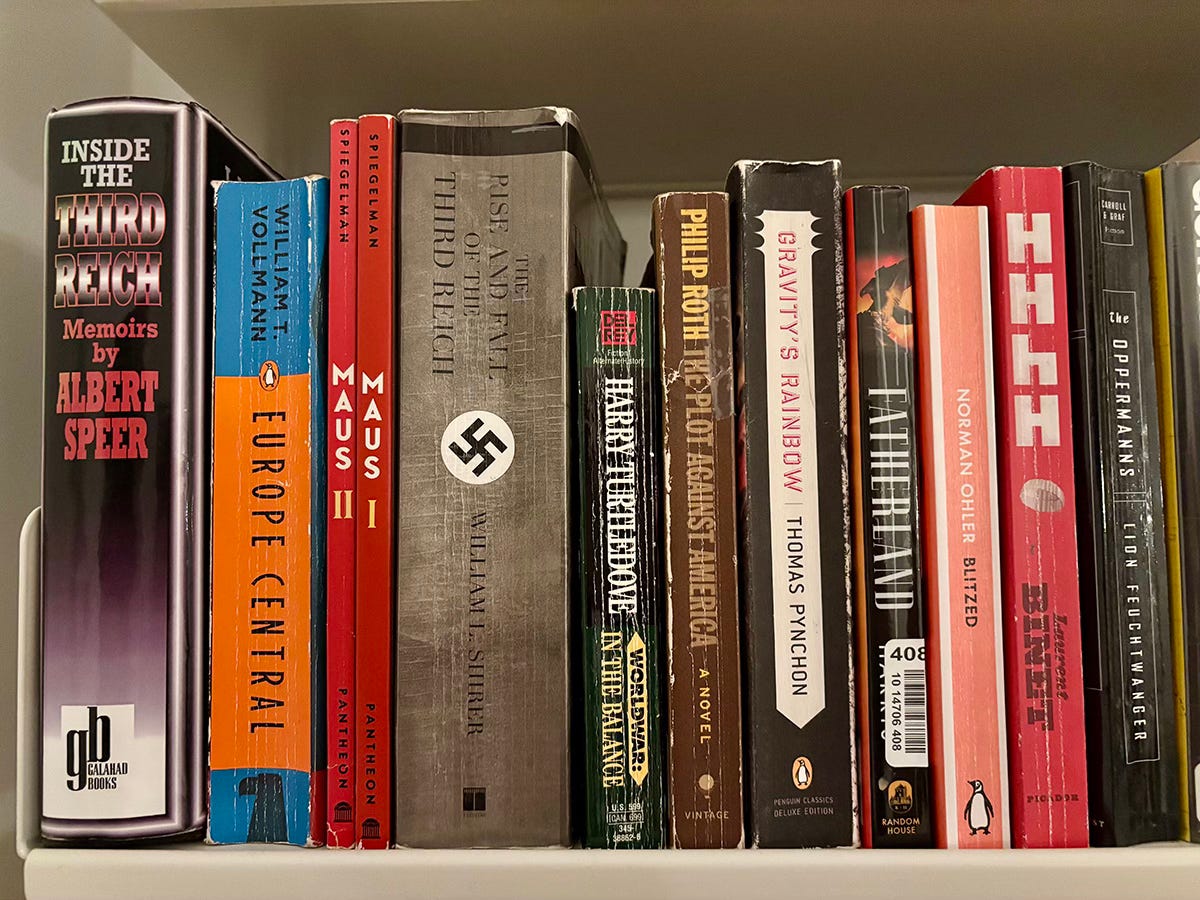

The gradual part: I started getting interested in religion from a purely intellectual perspective. In my youthful smugness, I’d rejected something I knew very little about, when of course not believing in something isn’t a good reason to avoid learning about it entirely. I don’t believe in Nazism either, but I’ve still read so many books about the Third Reich that they have a dedicated section on my bookshelf.

Besides, I’d long prided myself on having a broad base of knowledge. Did it really make sense for me to know the specific meal Richard Nixon ate the day he resigned, but have no idea what happens in Deuteronomy? Pretty much every human culture ever has developed some form of religion. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s true, but it does mean there’s probably something there worth paying attention to.

So I read the entire Bible cover to cover; it turned out to be pretty boring, but I’m still glad I did it. And I found myself seeking out more works by religious thinkers, or at least reacting with something other than immediate dismissal when I happened to stumble across them. I didn’t come away a convert, but I was left very curious about what it’s like to have a deep, genuine religious faith. If we ever develop some kind of high-fidelity sci-fi brain simulator, that’ll be the first program I download after I get bored with all the sex stuff.

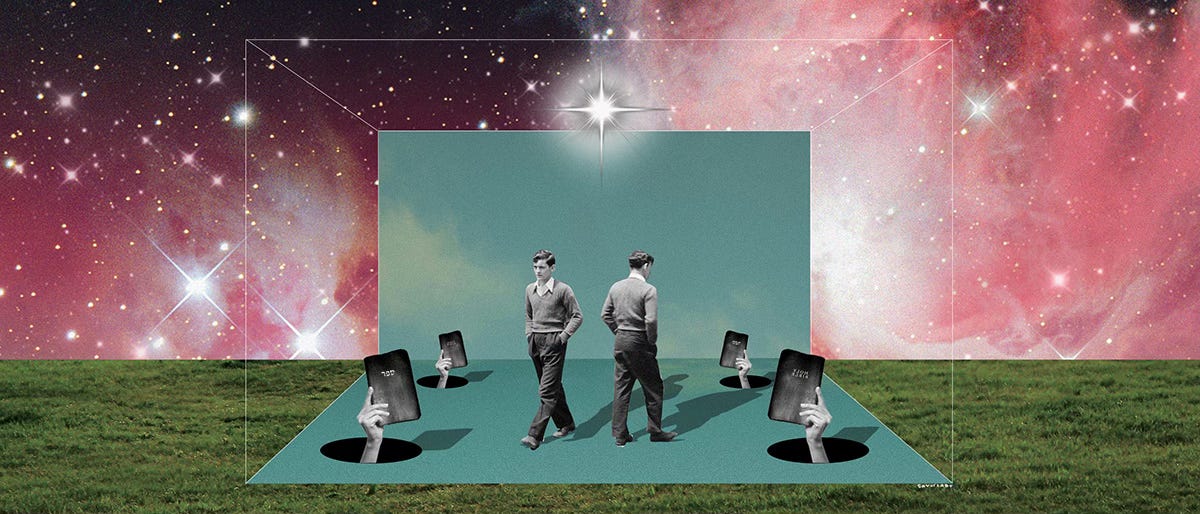

The sudden part: I drank ayahuasca out of an empty Gatorade bottle with a dozen strangers and a Peruvian shaman on an old hippie’s farm outside San Francisco. I didn’t do it because I was looking for god—I didn’t do it for any reason at all, really, besides idle curiosity. The opportunity presented itself, as such opportunities tend to do in the Bay Area, and I said yes because it seemed more interesting than saying no.

Two of the most annoying things to read about are spiritual revelations and psychedelic experiences, so I won’t risk my subscribers’ wrath by going into too much detail about a night that combined both. Suffice it to say that, for a few brief moments right after I’d finished vomiting in the dirt, I was certain I’d touched the face of something I could only describe as god.

Maybe that experience was so powerful that it would have shaken even the most insistent materialist. Or maybe it was just the final block pulled from my Jenga tower of nonbelief. Either way, as I drove home Sunday morning, I realized, to my great amusement, that I no longer thought of myself as an atheist.

That experience got me to stop calling myself an atheist. But it didn’t get me to start calling myself anything else.

It’d take a lot more than one night on a farm to turn me into a full-on religious believer. Nor can I bring myself to identify as agnostic, a word that’s always filled me with an admittedly irrational hatred. It’s a weasel word, the sign of someone who hasn’t given the issue sufficient thought, or is just too much of a wuss to admit they’re an atheist. Agnostics aren’t sure what they believe; I am sure what I believe, it’s just that what I believe is that I’m not sure. I know those two sentences sound like they both mean the same thing, but I swear there’s a difference in my mind.

In a lot of ways atheist still feels closest to where I’ve actually landed, at least for now, which is that there probably isn’t a god in any traditional sense, and that if there is something bigger and mysterious out there, it’s almost certainly so different from what people typically mean by “god” that using the same word feels like stretching language past its breaking point. But calling myself an atheist implies a level of certainty that no longer sits right.

Maybe I’m an atheist the same way Bill Clinton was a stoner: he smoked pot, but didn’t inhale; I saw god, but didn’t believe. Or maybe I’m an atheist the same way I’m straight: there’s that one blurry night that I just don’t count.

I suppose it’s a victory for atheism that the uproar over books like The God Delusion now seems wildly old-fashioned. Culture moves on, and nothing stays controversial for long: Ice Cube went from killing cops to hanging out with Elmo, and you’ll hear all seven of George Carlin’s dirty words you can’t say on television in ten minutes of Succession.

It’s not so much that the atheists won as that the whole question just stopped feeling important. Or at least, it did to me. After that weekend on the farm, my friends all asked if I’d been hit with any earth-shattering revelations, and I was never sure how to respond. On one hand, you could say that whether or nor there’s a god is the single biggest question facing humanity; on the other, wavering on my answer to that question had zero practical impact on my life. What you believe matters a lot less than what you actually do, which is probably why so many religious traditions emphasize practice even in the absence of faith.

If there is a god who experiences anything close to human emotions, I can’t help but imagine it wouldn’t really care whether we believe in it or not, and would likely be highly amused by all the time and energy we spend on the question. For all we know, god spends most of its time observing geological formations, and we’re just those unimportant monkeys who occasionally mess up the rocks.