Must Love Jobs

A secondary consequence of the pandemic has been the increasing number of books, articles, and podcasts about our supposedly-changing relationship to work. I’m inundated with a new one almost every day: apparently we’re all retiring early, changing jobs as part of the so-called Great Resignation, and just generally re-evaluating the role of work in our lives. “The pandemic,” says The Atlantic, “has downgraded work as the centerpiece of our identities.”

And so in this context I too have been thinking a lot about my own relationship with work.

When I was 24 and a brand-new startup founder, my work was absolutely the centerpiece of my identity. I constantly worried that I wasn’t obsessed with it enough, even as I watched it take over my entire life. There’s this pervasive idea in startup culture that founders need to be obsessed with their business in order to succeed, but I don’t think this ethos accomplishes much besides making beginner founders feel bad about themselves. Yes, the most successful founders do tend to be obsessed, but that obsession is a result of success, not its cause. A thriving startup naturally expands to fill more and more of your mindspace. And it’s never easier to be obsessed with your work than when things are going well.

But even when I was at my most obsessed, I wouldn’t have necessarily said that I loved my job. On a meta level, I liked the process of figuring out what things had to be done, and then figuring out a way to do them, but that didn’t mean I actually enjoyed doing most of those things themselves. Again, though, I think this may be a case of getting cause and effect backwards. Perhaps love isn’t the feeling that motivates our actions, but rather the word we use to describe the accumulation of those actions over time, even—or especially—when we don’t feel motivated. I must have loved my job back then, this logic goes. Otherwise why would I have poured so much of myself into it?

In a futile attempt to make this newsletter at least slightly less myopic, I talked to a number of people in my life about their relationship with the idea of “doing what you love.” There wasn’t a single person who uncritically embraced the concept—and yet it’s an idea every single one of us is intimately familiar with, usually to the point of cliché.

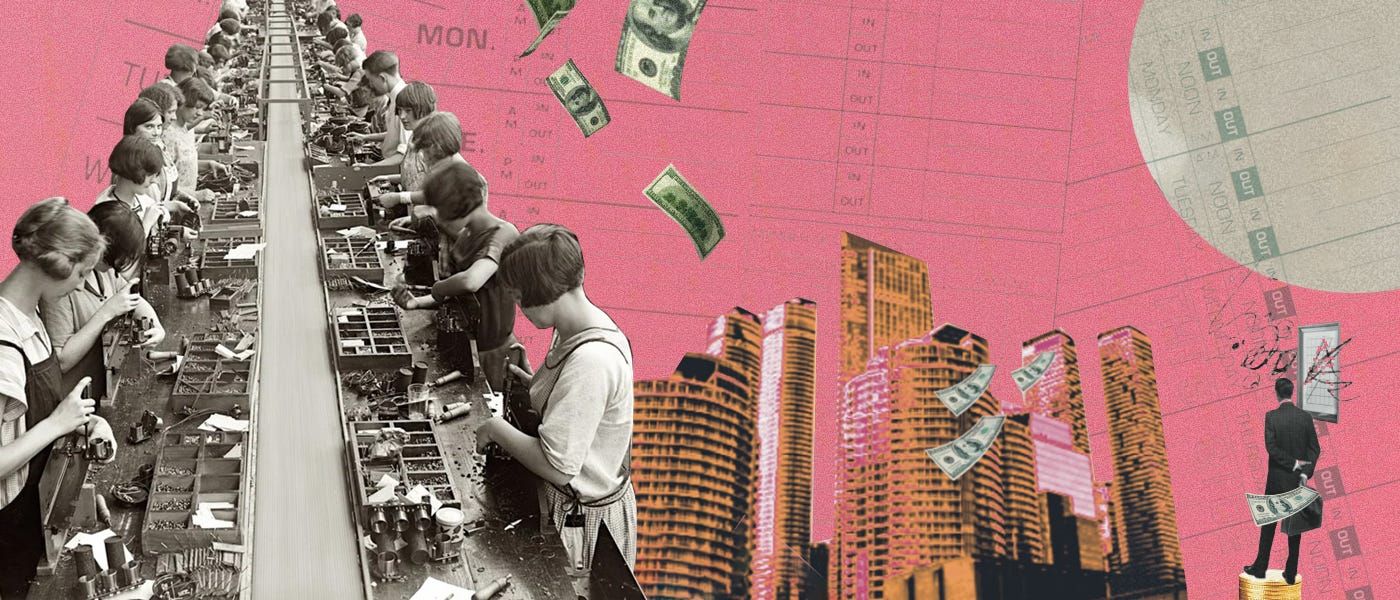

So if none of us really believe in it, why does this idea remain so pervasive? In my “research” for this piece, I encountered a number of labor activists and reporters—people like Sarah Jaffe, author of the recent Work Won’t Love You Back—who see the idea of loving your work as essentially a capitalist scam, created by the managerial class to con employees into working harder, for less money, and in worse conditions than they otherwise would.

But although it’s true that such an outcome is sometimes the result of people loving their work—or just thinking they should—I don’t buy that this idea was intentionally created for such purposes. For one thing, the people who seem the most preoccupied with finding meaning in their work tend to be highly-paid, white collar workers, who are clearly among the main beneficiaries of modern-day capitalism, even if they may technically still be “labor” in a traditional Marxist analysis. More importantly, though, it just isn’t that easy to incept an idea into people’s heads like this. I might be more sympathetic to this theory if these mythical capitalist masterminds had actually convinced us all that we love our jobs. But we don’t—we just often think we should. I don’t see how the anxiety generated by this cognitive dissonance benefits anyone, rapacious plutocrat or not.

When corporate leaders try to sell the rank and file on how much they’ll love their work—or when I myself did the same thing as a CEO—I see them as responding to a sort of “market demand” for meaning that originates with the employees. We insist on meaning, and so they do their best to give it to us, even if the result is usually a shallow simulacra of the real thing.

As for why we want it ourselves, that’s harder to say. Maybe the decline of other sources of meaning like religion and civic organizations has led us to seek it elsewhere, and the place we spend the majority of our waking lives is a natural one to turn to next. Maybe it’s easier to pretend we work because we love it, especially for the most privileged among us, than it is to acknowledge that on some level we do it because we’re forced to. Or maybe deep down we know that all of life is meaningless and so, like an addict scraping for crumbs in the couch cushions, we desperately scramble to find some anywhere we can.

In my startup’s waning days, I only became more obsessed, in much the same way you might cling even more desperately to a failing relationship once you start to realize it’s failing. If we were going to go down, I didn’t want it to be for lack of trying. But as I get further and further from that time in my life, the person I was then increasingly a stranger, I become less and less eager to ever go back to that kind of relationship with my work. These days, I’m kind of like a person who went through a bad divorce and ended up hesitant to ever get married again.

These days I’m very happy at my job, but I no longer see love as a relevant or effective metaphor for that relationship. If, when I was a founder, my job and I were passionate lovers, my current job and I are friends with benefits: we have an affectionate but transactional relationship, with clearly defined boundaries. I want my job to be a positive presence in my life, but it’d be a problem if I started to catch deeper feelings.

Still, though, I’d be lying if I said there weren’t times when I longed for the oblivion that comes from pouring 100% of yourself into a project. And in my own roundabout way, I suspect I’ll end up finding myself there again someday. After all, part of the reason I maintain a more relaxed relationship with my job these days is so I can have the time, and the headspace, to write things like this. This newsletter isn’t a job, but I treat it like one. And although I wouldn’t necessarily say I love it, I am committed to it. Which, in the end, is probably more important. After all, love is easy. But commitment is harder.

Yours in realizing I mixed like three different relationship metaphors in there a couple paragraphs back,

Max