Public Interest Law and the Paradox of Justice by Lawsuit

In which Ralph Nader kickstarts a new kind of political activism and accidentally paralyzes the government

This piece was originally published in Astral Codex Ten, where it was a finalist in this year’s book review contest. (It’s been lightly revised since then.)

How did we end up in a world where every new public works project is completed years late and billions over budget? Where so-called “environmental review” is weaponized to block even obviously green initiatives like solar panels? Where it takes longer to get approval for a single new building in San Francisco than it did to build the entire Empire State Building?1

Such a complex set of dysfunctions must have an equally complex set of causes. It took us decades to get into this mess, and just as there’s no one simple fix, there’s no one simple inflection point in our history on which we can place all the blame.

But what if there was? What if there was, in fact, a single person we could blame for this entire state of affairs, a patsy from the past at whom we could all point our censorious fingers and shout, “It’s that guy’s fault!”

There is such a person, suggests history professor Paul Sabin in his new book Public Citizens: The Attack on Big Government and the Remaking of American Liberalism. And that person isn’t isn’t a mustache-twirling villain—he’s a liberal intellectual. If you know him for anything, it’s probably for being the reason you’re familiar with the term “hanging chad.”

That’s right: it’s all Ralph Nader’s fault.

How’d he do it? By creating what’s now called the public interest movement: a form of activism through which citizens force change—or, more often, block change—by suing the government. Though it was begun with the best of intentions and achieved some real good along the way, this political innovation led to the constipated governance we all complain about today.

How did a movement launched by an unassuming 30-year-old lawyer become the dominant form of activism in the country, and completely change the way our government operates?

To find out, we have to go back to a time before Ralph Nader had even hit puberty—the era of the New Deal.

In the beginning, there was the New Deal.

Okay, so a lot of stuff happened in American history before then. 157 years of stuff, if you count from the Declaration of Independence, or 13,000 years of stuff, if you count from when the first human settlers are estimated to have come to North America.

But the current era of American history didn’t really begin until the New Deal in the mid-1930s. The scale of the transformation was staggering: dozens of major bills and federal agencies, including the SEC, the FHA, the FDIC, Social Security, minimum wage, collective bargaining, and the FDA’s drug-licensing powers all date back to the New Deal. Within just a few years, the federal government went from playing a largely hands-off role in the economy to touching almost every part of it.

The men who created the New Deal had an unshakeable faith in the power of experts. That’s why the New Deal relied heavily on a new model for delegating congressional powers: Congress would create a federal agency with broad latitude, then they, or the president, would staff that agency with outside experts. Freed from the grubby pressures of the political process, these agency men—and they were pretty much all men—would use their expertise to reshape the country2.

The Tennessee Valley Authority is the canonical example of a New Deal agency. Founded in 1933, it was designed to modernize the poverty-stricken Tennessee Valley3, with a broad mandate including electricity generation, flood control, fertilizer manufacturing, and general economic development. Here’s what it didn’t have to do: run its plans for the valley by any of the people who actually lived there. Although the TVA was broadly popular and is still considered a success today, its development plans displaced over 125,000 residents, who had essentially no recourse. Its first leader, displaying the lack of modesty that was characteristic of the era, described the agency’s work by saying, “What God had made one, man was to develop as one.”

There was, of course, some conservative pushback to FDR’s grand plans, and by the 1940s Republicans had managed to push through a law that guaranteed a public comment period and at least some judicial review of agency rules. But for the most part, these agencies were thoroughly integrated into our politics, and the American economy settled into a relatively stable equilibrium. In his 1952 book American Capitalism4, John Kenneth Galbraith summed up this equilibrium via the concept of countervailing powers: big government, big business, and the big unions worked together to collaboratively manage the economy.

By the 1960s, the cracks in this model were starting to show. A report prepared for President-elect Kennedy outlined the problem of regulatory capture, the process by which agencies intended to regulate private businesses got too close to their subjects and end up serving them instead5. And a new class of liberal intellectuals rose to prominence by pointing out the ways in which the political establishment’s plans sometimes rode roughshod over the citizens they were supposed to serve. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring criticized the USDA’s indiscriminate use of pesticides, and Jane Jacobs’ grassroots movement successfully blocked Robert Moses—the ultimate agency man—from ramming a highway through the West Village.

For all their accomplishments, though, Carson, Jacobs, and other activists in their mold tended to stay in one lane. Their objections were to specific government plans, not to the entire structure of the plan-making apparatus. It would take someone who thought a little bigger to uproot the New Deal agency model entirely.

Ralph Nader was born in 1934 to a pair of Lebanese immigrants in Winstead, Connecticut. Many prominent activists have dramatic origin stories, but not Nader: his family was well-off, and as far as I can tell, he had a happy childhood. The family did, however, have a moralizing strain: when Nader was offered a scholarship to Princeton, his father forced him to turn it down on the grounds that their family could afford to pay6.

By his early twenties, Nader had become something of a hotshot at Harvard Law School, where he developed an interest in vehicle safety after one of his classmates was injured in a car crash. Post-World War II, highway construction had boomed and vehicle sales had boomed along with it, with U.S. car ownership tripling in the two decades following 1946. But these cars were also pretty dangerous, with a per-capita vehicle death rate more than twice today’s. At Harvard, Nader proposed the then-groundbreaking, but now widely accepted, “double-injury theory”: the idea that a car accident is best conceptualized as consisting of two separate injuries, first the car itself hitting something and then the passengers hitting the inside of the car7.

After graduating, Nader moved to D.C. to work for Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who would later become a powerful senator and the namesake for a disappointing train station but who at the time was JFK’s Assistant Secretary of Labor. Moynihan was also interested in auto safety, and he even had a contract to write a book about the issue modeled on Upton Sinclair’s meatpacking exposé The Jungle, but he never ended up completing it.

Into the void stepped Nader, who readily agreed to take over the contract. The resulting book, Unsafe at Any Speed, was published in 1965. It documented the way car manufacturers avidly resisted even simple safety improvements, and pushed for a cultural shift away from blaming accidents on individual drivers towards a more epidemiological approach that saw car accidents as a public health issue.

Unsafe at Any Speed was a modest success, but it didn’t make too much of a stir—until, that is, it came out that in their zeal to discredit Nader, GM had hired a team of private investigators to dig up dirt on him, even enlisting a few young women to seduce him in an attempted entrapment8. Thanks to Nader’s ascetic lifestyle and complete lack of any interests outside of work, they failed spectacularly at getting anything compromising on him. But their clumsy attempts at subterfuge did manage to make Nader famous and his book a best-seller. Less than a year later, LBJ signed the Traffic Safety and Highway Safety Acts, largely due to Nader’s advocacy.

Almost single-handedly, Nader had kickstarted a new era of automotive regulation and set in motion a process that would make cars dramatically safer (albeit, unfortunately, also dramatically less cool-looking). He’d won a battle with the country’s largest company, and along the way he even got to hook up with some sexy women on GM’s dime.

Just kidding—when GM’s women invited him back to their apartment, ostensibly to “discuss foreign relations,” he suspected entrapment and declined. But he did later tell a reporter, in one of his rare attempts at humor, that “normally I would have obliged.”

At this point, the usual thing for someone in Nader’s position to do would be to write another book and continue their path of individual activism. But Nader had grander plans. He decided to become a new kind of entrepreneur—a self-appointed “lobbyist for the public interest” who’d spread his unconventional ways among other activists.

So he started a new organization dedicated to doing just that: the Center for the Study of Responsive Law. His newfound fame enabled him to recruit a prestigious group of young lawyers from elite schools, including President Taft’s great-grandson and Ed Cox, who married Richard Nixon’s daughter while working for Nader. “It’s like you’re looking at the names of the Pullman cars,” said one of Nader’s early employees, in a joke that today requires so much explanation I almost regret including it in this piece9.

Now that we live in the world Nader created—where over 10% of the American private sector workforce is at nonprofits—it’s hard to see how groundbreaking this was. The 501(c)3 hadn’t even been created yet; what few such organizations existed tended to be structured around the interests of specific identity groups and, below the level of top leadership, staffed mostly by volunteers, like the NAACP and the League of Women Voters.

Nader’s group was different: an advocacy organization with an employee base of full-time professionals, dedicated to the interests of the American public at large (or at least, what they saw as the interests of the American public)10. In 1969, when the group started researching their first project, the Christian Science Monitor wrote:

So far as anyone can remember, nothing quite like this has happened in Washington before. A group of unofficial but informed outsiders…as a sort of civilian posse, has descended on a rather stuffy government commission, poked under sofas, and asked some rough questions.

A Washington Post columnist nicknamed the group “Nader’s Raiders,” and it stuck.

The Raiders decide that their first target would be the Federal Trade Commission, which Nader believed had become too cozy with the businesses it was supposed to regulate and failed to live up to its ostensible mission of protecting the American consumer. They quickly wrote and released a blistering report that, among other things, accused the FTC of being rife with “alcoholism, spectacular lassitude, office absenteeism, and incompetence by even the most modest standard.”

Nader and his employees were pretty much all liberals. But they were liberals of a different sort than the ones who created the New Deal. The Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement (and, later, Watergate) had caused them to lose faith in government, and they were distrustful of so-called “experts” and of centralized power in general11.

This distrust was why they operated through their own independent organizations, rather than by running for office or working with existing groups like the labor movement. Many of them were followers of the radical organizer Saul Alinsky, who emphasized an explanation for leadership failures that focused on structural issues, not individual choices. “Through experience,” Alinsky wrote, “you learn to see people not as sellouts and betrayers. [Morality is] largely a rationalization of the point you happen to occupy in the power pattern at a given time.”

In other words, it wasn’t simply a matter of getting the right people into power, as the very act of getting into power would mean they were no longer the right people. The only way to stay pure was to operate outside the system.

Nader also believed that if you wanted to accomplish something, you shouldn’t attack your enemies—you should attack your friends. Your enemies, after all, already hate you. But your friends are incentivized to listen. As such, his group’s FTC report primarily criticized Democrats. And Democrats were pissed. Speaker of the House Jim Wright later wrote that Nader was like a rookie football player who thinks you win games by tackling your own quarterback.

But Nader’s theory had legs. In the fallout from the report’s release, Congress gave the FTC expanded powers and mandated citizen participation in its decisions. His team soon ran the same playbook with, among many other things, workplace safety and air and water pollution. Their advocacy was instrumental in passing the Clean Air Act (1970) and Clean Water Acts (1971), two of the largest pieces of environmental legislation of all time12.

The Clean Air and Water Acts had major differences from previous laws of their type, spurred by what Nader believed were flaws in the older approach. Although these laws continued to rely on agencies staffed with outside experts, they rejected the New Deal style of fully deferring to them. Instead, they gave the agencies they created extremely detailed mandates, procedures, and timelines. They required judicial review of agency decisions, and explicitly empowered citizens to sue the agencies for not following the rules. (Previously, it wasn’t clear that a random individual American would have standing in such a case.) As one of Nader’s top men said, these new laws were designed to be “government-proof.”

If Nader was famous after Unsafe at Any Speed, he became even more famous now. And his dream of getting more lawyers into public service had succeeded beyond his wildest expectations. In 1968, he gave a barnburner of a speech with a title that sounds like it was taken from a fantasy novel: “Law Schools and Law Firms: The Mordant Malaise or the Crumbling of the Old Order,” which railed against law schools for corrupting young lawyers. The next year, an entire one-third of Harvard Law’s graduating class applied to work with him.

This was despite the fact that Nader was, by all accounts, an absolutely atrocious boss, someone who had no interests outside of work and a nonexistent personal life. He never married or, as far as I know, had any romantic relationships whatsoever, ostensibly so he could devote himself to his career full-time. He pushed his employees to work hundred-hour weeks and was notorious for calling them while they were on vacation and berating them for not working.

By the mid-seventies, Nader was at the height of his influence. George McGovern briefly considered him for vice president, but Nader said no, and also refused entreaties to run as a third-party candidate—at this point, he was staunchly against getting involved in electoral politics. After Jimmy Carter received the Democratic nomination in 1976, he took a three-hour meeting with Nader, where Nader spent the entire time lecturing him about how government “really” worked. Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell said, “Nader is the single most effective antagonist of American business,” which Nader probably took as a compliment.

But his real influence lay in the many other groups his example inspired. Some, like the Environmental Defense Fund, were explicitly modeled on Nader’s organizations. Others, like the Sierra Club, long predated Nader but began copying his tactics. The number of active nonprofits tripled during the 1970s.

Initially, the vast majority of these groups were left-leaning, but pretty soon conservative activists got in the game too. And why wouldn’t they? Although he’s often caricatured as a radical liberal, there was something very small-c conservative about the way Nader and his ilk operated. They were heavily distrustful of government and spent most of their time either publishing reports criticizing the government or just suing the government directly. (In the first two years of the Nader-inspired Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, a whopping 70 of their 77 lawsuits were filed against the government!) And the laws they help craft were designed with that distrust in mind.

Except it’s not totally accurate to call it a distrust of government. Because while, in Nader’s view, the legislative and executive branches may have been inevitably pulled towards corruption, there was one branch he and his allies did trust: the courts. Nader’s philosophy was one of justice by lawsuit. Make it easy for individual citizens, or the groups representing them, to sue, and the legal process will handle the rest. It was like Nader and his team had discovered a cheat code to punch way above their weight class. Litigation, said the Environmental Defense Fund, produced results “faster than by lobby, ballot box, or protest.”

And those results were often spectacular. Like when the Nader-founded Center for Law and Social Policy sued to stop construction of the Trans-Alaska pipeline under the new (and Nader-influenced) National Environmental Policy Act. CLASP, less than two years old when the lawsuit was filed, had only a dozen or so employees. And yet they managed to obtain an injunction that halted construction of the pipeline for several years.

The world (or at least, the small part of it that paid attention to this sort of thing) was stunned. A tiny law firm that most people in DC hadn’t even heard of had, for the time being at least, stopped one of the largest and most ambitious engineering projects in American history.

And so on, and so on, and so on. Nader and his acolytes spawned generations of copycats and they sued and advocated and sued and advocated and in response, we blanketed government agencies under new layers of rules that constrained how they could operate. The public interest movement wasn’t the only force behind this push for procedure, of course. But it was a major one.

Eventually we got to the America of today: one with tens of thousands of public interest nonprofits, and one where an ambitious young person who wants to make a difference in politics is far more likely to join a nonprofit that sues the government than to join the government itself.

Individually, the changes the public interest movement pushed for—among them, comment periods for rulemaking, thorough environmental review, pre-enforcement review of agency rules, and ubiquitous court challenges—seemed like reasonable ideas. But collectively, they stymied the government's ability to do anything. Ironically, the very policies the progressives of the seventies helped put in place now stand in the way of the government action today’s progressive movement demands.

And in hindsight, Nader’s belief that stricter procedures could prevent regulatory capture seems hopelessly naive. As it turns out, reducing agencies’ discretion and layering on detailed processes doesn’t actually prevent the wealthy and powerful from taking advantage of the system. If anything, additional bureaucracy actually further enables such manipulation, since only the most dedicated and well-resourced actors can effectively game complex procedures.

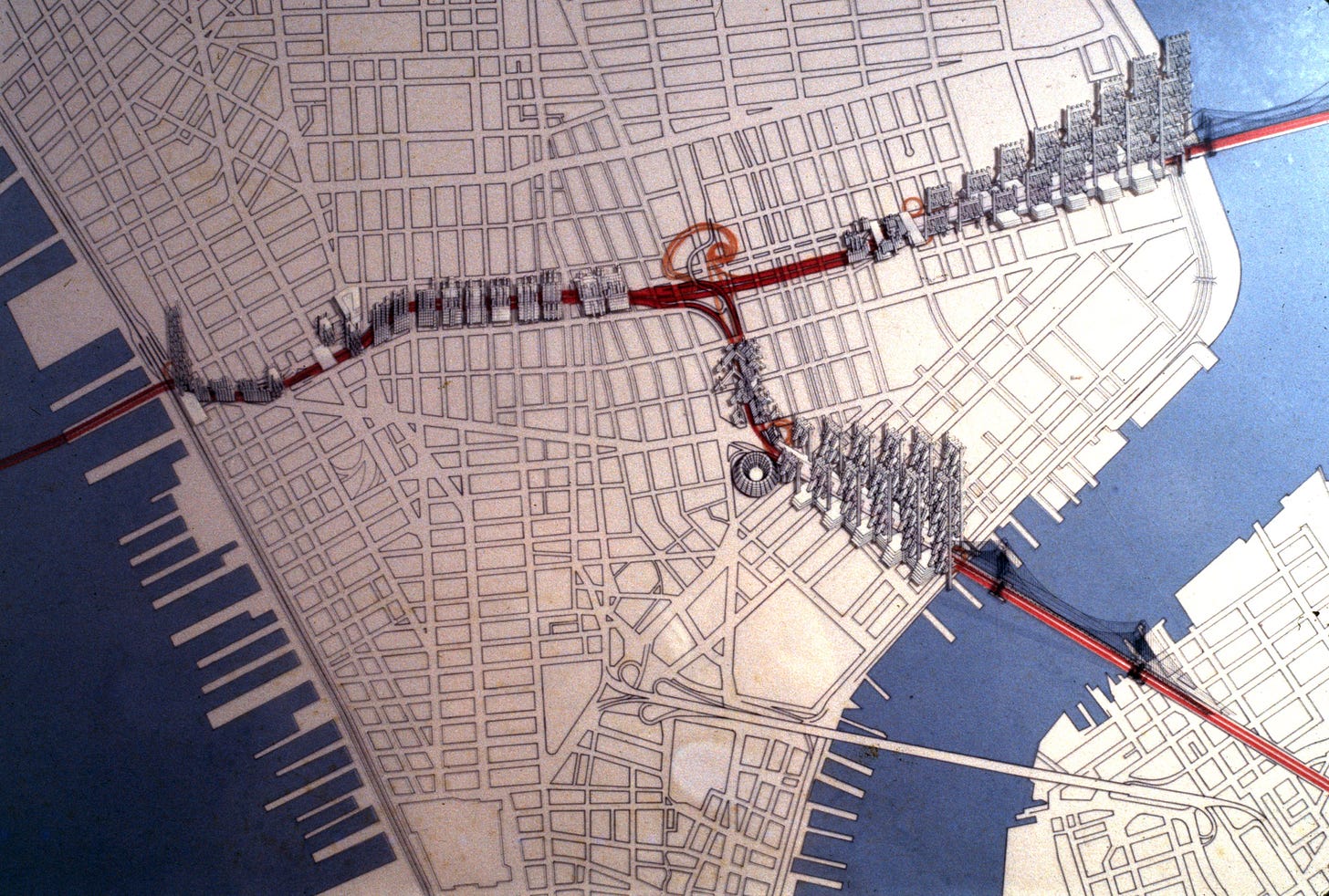

Today, business groups dominate agency notice and comment periods, submitting almost ten time as many comments as public interest groups or individual citizens13. Industry submits over 80% of all comments to the EPA. And the Freedom of Information Act—championed by Nader, and hailed as an unprecedented mechanism for government transparency when it was passed in 1966—is today mostly used by businesses for profit-making purposes14. Among the many projects blocked or delayed by lawsuit activism—or the excessive legal review designed to preempt it—are public transit in Hawaii, wind farms on Cape Cod and upstate New York, and NYC congestion pricing, not to mention the millions of new homes around the country we should be building but aren’t.

The public interest movement’s legalistic approach also came with hidden costs. Their theory of change rested on the intense efforts of a small group of educated, elite insiders. As such, their fights often happened behind the scenes—they may have been acting in the public interest, but that didn’t always mean the public was interested. And their arguments, tuned for the courtroom, often relied on technicalities rather than on broad theories of justice.

But the courts are better at tearing down than they are at building up. Nader’s movement stopped or delayed a lot of things it was against, but it was much less effective at painting, let alone implementing, a positive vision of what should be built in their place.

Single-mindedly pursuing this inside-game strategy also came at the expense of coalition and movement-building, which left many of these groups’ victories flimsier than they first appeared.

I don’t think it’s any coincidence that Nader’s most effective and enduring impact on American society—the push for auto safety that first made him famous—is also the one where, through TV appearances and his book, he built the broadest base of public support. Yes, the legislation he pushed for established stricter standards for how cars were built and tested. But the reason that legislation hasn’t been neutered by loopholes—and the reason those standards have continued to get tougher and tougher in the sixty years since—is because a majority of the public was convinced of Nader’s views.

Still, I don’t think any of this means Nader and his allies were necessarily wrong to pursue the strategy they did. The changes the public interest movement wrought did a lot of good, and it would be a mistake to suggest we’d have been better off without it just because the changes had some unintended consequences.

Besides, some of this backsliding was probably inevitable. The history of governance is one of constant see-sawing: we confidently implement a change we’re sure is going to fix everything, only to discover it has unexpected loopholes or unforeseen side effects. We get rid of earmarks to reduce corruption, only to find we’ve gummed up the works of Congress by removing an essential dealmaking tool. We push for open primaries to reduce the influence of men in smoke-filled rooms, only to find that we’ve opened a path to power for populist demagogues. And we create independent agencies staffed by outside experts who we think will be immune to the sleaziness of the political process, but they end up insufficiently responsive to the will of the people, so we add a bunch of rules and regulations to give the public a greater voice, but they end up monopolized by a small minority or stifling the agencies’ ability to accomplish anything at all.

It is the inherent nature of politics that no reform works forever, because the next generation of political entrepreneurs will inevitably discover new ways to bend the process to their will. Eventually, there will always be another Dick Fosbury revealing a way to work the system that no one saw coming.

Still, I do think some of the blame for the way this all panned out can be laid on Nader’s particular personal idiosyncrasies. His ironclad black-and-white view of the world, combined with his near-pathological aversion to dealmaking and compromise, made him uniquely suited to a form of activism that focused on regulatory and legal action rather than coalition-building and electoral politics. Nader was infamously rigid and inflexible, so it’s no surprise that his movement was too. But a less rules-oriented movement might have created fewer of the bureaucratic barriers that have now become a hindrance to progressive action.

Much like the movement whose story it tells, Public Citizens the book is a worthwhile project that nonetheless suffers from significant flaws. The main problem is that it can’t decide if it’s a historical narrative or a work of political theory. As a work of political theory, it doesn’t take nearly a strong enough stand—I’ve made explicit a lot of claims that are only lightly implied in the book. I think we’re making the same argument, but the book makes its claims with such a delicate touch that it’s hard to be 100% sure.

As a historical narrative, Public Citizens has a much simpler problem: it’s boring. The author writes like the academic he is, and the book is quite light on colorful details. The uncreative chapter titles (chapter three is called “Creating Public Interest Firms”) give you a taste of what the writing is like. One particularly egregious issue is how little biographical information is provided about Nader, even though the majority of the book is about him. For someone who apparently subscribes to the Great Man theory of history, the author includes surprisingly little information about the Great Men themselves. Any interesting biographical fact you read in this review—even something as basic as the fact that Nader never married—is almost certainly something I found through other sources.

Paradoxically, this book manages to be simultaneously boring and too concise. It’s over in less than 200 generously-spaced pages, and I frequently had to look stuff up on the internet to get a full understanding of what was going on. I get the sense that the author is trying to give this book mass appeal, but come on: anyone who’s willing to read a nerdy book like this is willing to read an additional hundred pages or so. Besides, Robert Caro and Ron Chernow have proven that people will read thousand-page tomes if the story is compelling and the details are juicy.

Basically, my critique of Public Citizens is like that old Catskills joke about the restaurant where the food is terrible—and the portions are too small.

We’re now over four thousand words into this review, and I’ve barely even mentioned the 2000 election. While that infamous debacle isn’t a core part of this story, I do think it’s worth a quick postscript. How did someone like Nader—a staunch believer in staying outside the system who repeatedly refused his supporters’ requests that he seek elected office—end up running a doomed third-party campaign, and in the process help elect a president who worsened America far more than Nader ever improved it?

The answer starts with Nader’s uncompromising moral worldview. There never has been, and probably never will be, a president who lived up to his extreme standards. Take Jimmy Carter: even though Carter granted Nader unprecedented personal access, and even though many Naderites had high-level positions in Carter’s administration, Nader did nothing but criticize him, and in fact actively undermined his re-election15. “Reagan will help [our movement]” by galvanizing the opposition, Nader predicted, comically inaccurately. Decades later he finally admitted that Carter had in fact been the most pro-consumer president of his lifetime.

So of course when the nineties came around Nader viewed the Clintons with equal disdain, oblivious to the fact that the anti-government liberalism he pioneered was part of what brought about “Third Way” Democrats like Clinton and Gore. Like that Rage Against the Machine video, he saw Bush and Gore as one and the same—“tweedledee and tweedledum,” he called them. Having learned nothing from the Reagan years, he once again inaccurately predicted that a Bush victory would actually be better for the country, because it would fire up the progressive movement.

But it really seems like another piece of the puzzle is that Nader just wanted attention. Despite his unassuming nature, he loved the spotlight, and he’d been in it a lot less since the late seventies, when his career had peaked. Now here he was, on TV all the time and being treated like a major candidate. He bragged to Jim Lehrer that he was qualified to be president because “no one has sued the government more than me.”

Of course, I’m sure Nader would say that it was his ideas he wanted attention for, not himself. But if the movement was really all he cared about, he probably would have listened when twelve of his most prominent former acolytes wrote an open letter begging him to stop his kamikaze strategy of telling everyone there was no difference between the two major candidates. Not only did Nader ignore them, he doubled down, campaigning extensively in Florida as election day approached.

We all know how the story ends. Nader tipped the election to Bush, who did such a bad job that even his own party completely repudiated his legacy. The war on terror caused far more death and destruction than Nader’s seatbelt mandates ever prevented. And just like that other Bush, Jeb!, Ralph Nader ended his career as a joke, remembered more for his one epic faceplant than for any of his actual accomplishments.

At the time, it wasn’t a sure thing that this delegation of congressional powers was constitutional, but it has since become such a core part of how our government works that most people don’t even realize it only dates back to the 20th century. As Elena Kagan once wrote, “if [this kind of delegation] is unconstitutional, then most of government is unconstitutional.”

Government agencies don’t have very creative names.

Books by government employees usually don’t have very creative names either.

Many see regulatory capture as a process of straight-up corruption, but the report’s author—former Civil Aeronautics Board chairman James Landis—proposed a more subtle mechanism: after spending so much time with the people they’re regulating, regulators genuinely and honestly come closer to their points of view.

Don’t worry, Nader still made it to Princeton—presumably, his dad ponied up.

I’m still not sure why this was the kind of thing someone would study in law school.

GM still denies this last part, but it definitely happened.

Pullman made train cars; in the days before widespread air-travel, the super-rich would have private luxury cars with their names on them.

The one exception to this employee base: Nader himself. Recognizing that he was too prickly and independent to be employed anywhere, even at an organization of his own creation, Nader oversaw the center but didn’t technically work for it.

This is also why Nader, unlike many liberals of the era, never flirted with communism.

Fun fact that I couldn’t find a place for anywhere else: Nader distrusted unions for the same reason he distrusted all forms of centralized power, and he refused to work with them on his workplace safety advocacy. His skepticism was vindicated when he recruited an opposition candidate to run against the president of the United Mine Workers union, and the union boss had the opposition candidate murdered. Unions in the 70’s were crazy!

Technically, federal agencies don’t have to consider the volume of comments for or against a proposed rule, only the quality—but those same studies found that comments submitted by businesses are usually of higher quality as well. They can easily hire experts to help them craft thoughtful, well-researched comments, whereas the average citizen who closely follows agency rulemaking tends to be, well, a little nuts.

Including my own—my former startup occasionally used FOIA exactly like this.

Nader’s uncompromising criticism even extended to his friends in the government. When his old colleague Joan Claybrook, now head of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, took slightly longer than Nader wanted to implement a new airbag mandate, he publicly excoriated her.