Self on the Shelf

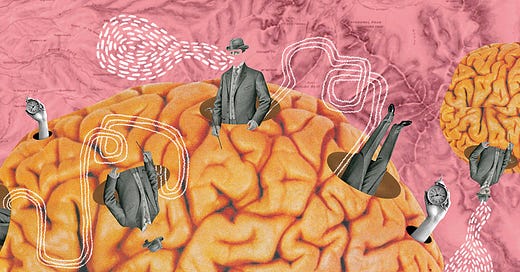

Derek Parfit, lost memories, and the conceptual incoherence of the unitary self

I’m often struck by how weird it is that we remember so little of our lives. To take just one example: if you count only actual, concrete memories—not loosely-felt senses of things, or the vague impression that I once did this or that—I have at most thirty or so real memories from my four years of college, supposedly one of the most foundational periods of my life. And half of them are stories I’ve told so often that my retold version has by now probably overwritten the original.

Weird, too, is the way we’re just as likely to remember nonsense as we are the important stuff. I have more vivid memories of sitting alone in my dorm room pining over various girls than I do of actually spending time with the girls in question. I have memory after memory of walking around campus listening to specific songs, hours and hours of mental footage of me with headphones, in just thinking. Meanwhile, entire friendships have been reduced to a mere handful of blink-and-you-might-miss-‘em images.

I know we can’t remember everything—the few genetic mutants who do inevitably describe it as a curse. But I have to wonder: if I can barely remember what it was like to be my past self, and I can’t remember most of what happened to him, then is it really accurate to say he’s “me” at all?

Throughout history, many philosophers, mystics, and guys who took too much acid have pondered this same question, and most arrived at the same conclusion: that no, our past (and future) selves aren’t exactly us. Or rather, that the entire concept of a singular personal identity, when you stare at it closely enough, starts to break down.

One such philosopher was Derek Parfit, famous for coming up with the repugnant conclusion (his term), and for eating the repugnant breakfast (my term), a concoction of sausage, green peppers, yogurt, and banana, all mixed together in one bowl, which he ate daily for many years.

All philosophers love thought experiments, and Parfit was no exception. He devoted a chapter in his 1984 book Reasons and Persons to a few designed to demonstrate the surprising brittleness of our concept of personal identity.

The first involves teleportation, which Parfit instead calls “teletransport,” probably so his thought experiment didn’t have to compete with all the Google results for teleportation. It goes like this: imagine a future world where teleportation is as widespread as air travel is today. These future teleportation machines work by making a particle-level scan of your body, then vaporizing it and instantiating a new one at your desired destination. This new copy has been made with such subatomic precision that it is indistinguishable from the original and includes all your memories. Your subjective experience is that you have simply disappeared and then re-appeared in a new location.

So: is the new version of “you” still you? What if the machine malfunctions and the new you is assembled before the old you is vaporized—are they both you? Should the “you” who is about to be vaporized be upset about its impending “death”?

Now imagine a diabolical weirdo who does the same vaporize-and-rebuild process on you, only he does it secretly, without your consent, while you’re asleep. (Parfit calls this character the mad scientist, but I think “pervert” would be more accurate.) Are you the same person the next morning as you were the night before the pervert’s visit? What if he does it gradually, over many years, Ship of Theseus-style? This thought experiment isn’t even that far-fetched: the cells in our body turn over completely multiple times a year. (Nature: the ultimate pervert.)

Parfit’s point was that there are no good answers to these questions, because “me” is a concept without clearly-delineated edges. It’s really more of a spectrum, a word that—like most words—refers not to a single thing, but to a loose bundle of related concepts. You can say that something is more or less you-like, but you can’t always say that it’s definitively you or not you. This is obvious when we talk about chairs, but it’s not always so obvious when we talk about ourselves.

In Parfit’s view, what makes another entity more or less you-like is the level of psychological connectedness it shares with your present self. The connectedness between your present self and the person you were earlier this morning is about as strong as it can get. But the connectedness between your present self and your ten-year-old self is less strong. It might even be weaker than the connectedness between your present self and your spouse, or your child, or a close friend—in which case those people might actually be closer to being “you” than some versions of your past self are.

In a way, Parfit’s ideas are closer to the non-Western conception of the self—or at least, the non-Western conception of the self as filtered through Western anthropologists. Here, we value individual autonomy and expect people to be consistent. Someone who presents too differently in different contexts is considered untrustworthy or two-faced, or else they’re code-switching, which is usually seen as an oppressive burden forced on minority groups by the dominant culture. But in many other places, the self is seen as existing not on its own but in the context of a location or a community, and you’d no more expect someone to be the same person in all contexts than you’d expect them to wear the same clothes in all weather.

But you might not even need philosophers or anthropologists to see how porous the self is. You might just need to look at your own hands.

Clip your fingernails and you probably stop seeing the resulting slivers as parts of you before they even hit the bathroom floor. But take an axe to your wrist and that’s still your hand bleeding out on the ground. So perhaps the self is like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous explanation of pornography: you can’t define it, but you know it when you see it1.

Of course, knowing all of this only gets you so far. The real question is: what should you do about it?

One answer might be: not much. I’ve found that this looser conception of the self is one of those things that’s hard to truly intuit, no matter how much I tell myself I believe it. Parfit himself said that he had to continually re-convince himself of the idea.

And of course, I realize there’s something ironic about my continually returning to this theme in a newsletter I’ve also used to craft a narrative around my own life. It could all just be a “doth protest too much” situation: perhaps, like many writers, I’m driven to narrativize myself like this because on some fundamental level I recognize that it’s all an illusion.

For what it’s worth, Parfit did think there were concrete benefits to internalizing the idea of a more porous self. One was reducing your fear of death: if “you” are just a series of psychological connections with others, many of those connections will remain even when your corporeal form is gone. He also found that redefining the self helped him feel more connected to others:

There is still a difference between my life and the lives of other people. But the difference is less. Other people are closer. I am less concerned about the rest of my own life, and more concerned about the lives of others.

To this list I’d add a third benefit: becoming better at embracing change. Perhaps we can cling less avowedly to our beliefs, habits, and routines once we understand that there’s nothing all that solid doing the clinging in the first place.

The funny thing about all of this, though, is that Parfit, by his own admission, got started down this path not through logical reasoning or thought experiments, but from circumstances that were deeply personal: he had even fewer memories of his past than I do, which he attributed to aphantasia, an inability to form mental images. In their absence, his connection to the person he used to be was weakened, and that got him thinking. He argued against its existence, but like the rest of us, he couldn’t escape the self.

“You” might not be a coherent concept, but you can still hit the little “like” button below to feed my fragile ego and help more people discover my writing on Substack. Also, if you enjoyed this one, you’ll probably like The False Promise of Understanding Yourself, a piece from last year that touches on some similar themes.

Fun fact: Stewart may not have been able to define pornography, but many of his fellow justices at the time sure could, and several proposed their own rules. Byron White thought that penetration of any orifice crossed the line, but William Brennan, who seemed to be a little confused about the mechanics of sex, thought penetration was allowable as long as the penis doing the penetration wasn’t erect. (I swear I am not making this up.) His clerks called it “the limp-dick rule.”