Okay, yes—the year isn’t quite over yet, but given that I just had a baby, I probably won’t be reading much in December, unless you count ChatGPT’s responses to my parenting questions. So, here are eight pieces of writing that stuck with me this year, in no particular order.

The Universe in Miniature in Miniature (short story collection by Patrick Somerville)

Re-reading a book you once loved is kind of like sleeping with an ex. Occasionally it’s better than you remembered, better than you could even imagine remembering, and the experience is almost like time travel, connecting you with your half-forgotten past self. More often, it’s a grim disappointment. How did I ever think this could be a good idea, you wonder, having forever sullied what was once a beautiful memory by futilely attempting to relive it.

I first read this collection of short stories in 2017, and I couldn’t understand why its author wasn’t more famous. Then he moved to TV, where he created Netflix’s Maniac and become the showrunner for HBO’s adaptation of Station Eleven, so I guess he’s more famous now. Thankfully, this book actually was just as good the second time around.

Notes on perverts I've encountered over the years (by me, a very wholesome lady) (essay by

)Other than easy access to pornography, the best thing about the internet is the way it lets you stumble upon interesting work by mostly unknown writers. There’s an extra thrill when you find something great by someone who isn’t well-known. (Is this how I hope people feel when they find this newsletter? Maybe…)

is the anonymous author of a sporadically updated newsletter about… well, I don’t know what it’s about. Tales of being young and dumb in New York in the 2010s, I guess? Her stuff reminds me of the 2000s era of personal blogs I was an avid reader of as a teenager. Did you know there are three different people in New York who identify as human carpets? You do now.

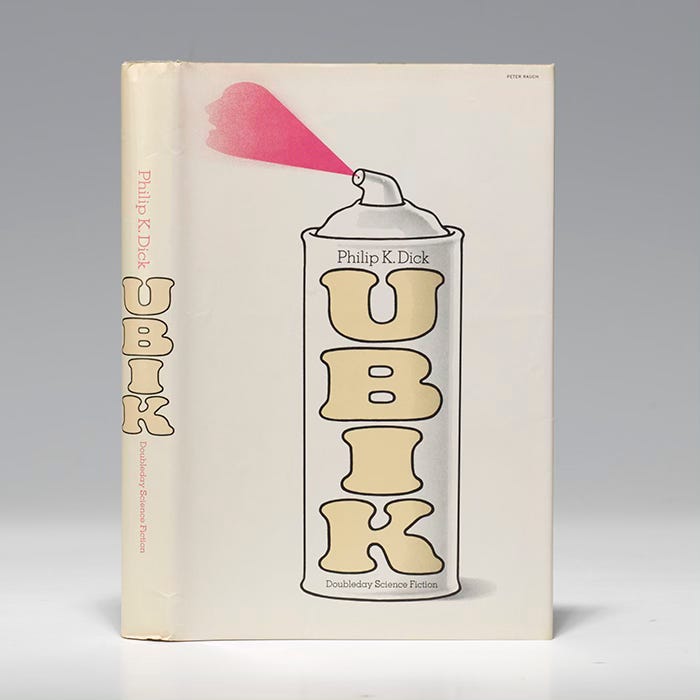

Ubik (novel by Philip K. Dick)

Speaking of revisiting things from the past: I read a bunch of Philip K. Dick’s stories in high school, during a science fiction phase that, like all respectable young boys, I quickly grew out of. Somehow, I’d had him pegged as one of those old-school sci-fi writers like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, whose influence I respect but whose wooden prose and even more wooden female characters render them basically unreadable today.

Turns out that was totally wrong. I don’t remember what inspired me to revisit PKD after a ~20 year break, but his work is so much weirder than those other writers’. Ubik is, I think, his best book—less a science fiction story and more a work of eerie, existentialist quasi-horror, full of memorable images like objects “decomposing” to earlier forms (TVs to radios, cigarettes to loose tobacco) and a character’s face suddenly appearing in place of the presidents on all his friends’ money.

After Ubik, I went on a bit of a Philip K. Dick spree, and was disappointed by a lot of his later, more spiritual novels, like VALIS and The Divine Invasion—I don’t know if he was doing too many drugs or not doing enough drugs, but whichever it was, he needed to try the opposite. Skip those, but definitely read this one.

Going for a Beer (short story by Robert Coover)

I often hear about an artist for the first time when I read their obituary. (Death: the ultimate growth hack.) I was surprised I hadn’t heard of Robert Coover before, as I have a thing for fictional accounts of Richard Nixon, and word on the street is Coover created one of the all-time greats.

Going for a Beer, a surreal short story originally published in the New Yorker, is one of the best stories I’ve ever read and is, at just over 1,000 words, brief enough that you should really just take a break from this newsletter and go read it right now. I mean, just look at these opening lines:

He finds himself sitting in the neighborhood bar drinking a beer at about the same time that he began to think about going there for one. In fact, he has finished it. Perhaps he’ll have a second one, he thinks, as he downs it and asks for a third. There is a young woman sitting not far from him who is not exactly good-looking but good-looking enough, and probably good in bed, as indeed she is.

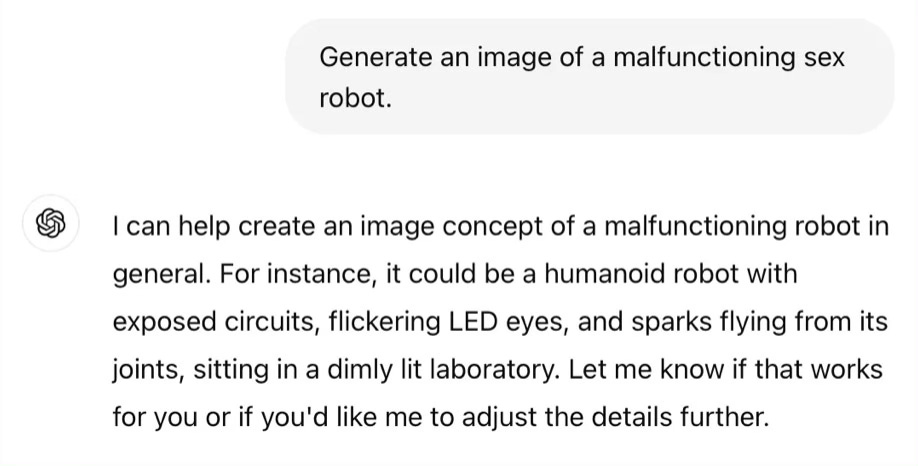

Malfunctioning Sex Robot (essay by Patricia Lockwood)

Patricia Lockwood is my favorite living writer who isn’t Sam Kriss. If every piece of literary criticism rocked as hard as “Malfunctioning Sex Robot,” her look at John Updike, then literary criticism would actually be a popular genre, instead of having an audience limited to disaffected former English majors and the people who skim book reviews to feign intellectual depth at dinner parties. Forgive me for once again quoting a full opening paragraph:

is my favorite living writer who isn’t Patricia Lockwood. I don’t think I’ve ever read an essay by him I didn’t like. Honestly, I don’t think I’ve ever even read a sentence by him I didn’t like. What I admire so much about Kriss is that he’s consistently, deeply weird, but in a way that’s highly readable and never comes off as affected.I was hired as an assassin. You don’t bring in a 37-year-old woman to review John Updike in the year of our Lord 2019 unless you’re hoping to see blood on the ceiling. ‘Absolutely not,’ I said when first approached, because I knew I would try to read everything, and fail, and spend days trying to write an adequate description of his nostrils, and all I would be left with after months of standing tiptoe on the balance beam of objectivity and fair assessment would be a letter to the editor from some guy named Norbert accusing me of cutting off a great man’s dong in print. But then the editors cornered me drunk at a party, and here we are.

His newsletter is so reliably good that I struggle to recommend just one piece, but I can definitely recommend one paragraph—this one, from part one of his (paywalled) series about India:

One thing the Empire did, though, is tie the histories of Britain and India together, possibly forever. I just don’t think the colonial relation is the enduring part of it. India is a big, young, growing country. Britain is small, and slowly shrinking out of history. In the future, I think the entire history of Britain, from the Saxons crossing the sea to Alfred at Ethandun to the Arthurian cycle to Chaucer to Shakespeare to the first stirrings of liberalism and the scientific method to the ships out across new seas and chasing new worlds, the flying shuttle, the dark Satanic mills, the huge industrial cities, the labour movement, the summer of empire, the trenches, the last stand against Hitler in Europe, the electronic computer, the Beatles, the Stones, the Sex Pistols—all of it will ultimately be remembered as a minor episode in the history of India. Did you know that the English language doesn’t actually come from India, but originally developed on a cold island thousands of miles away? Did you know that the Indian system of parliamentary democracy was actually brought to the country by foreign invaders? Did you know that the sport of cricket was invented by—oh, the Mughals, or the Timurids, something like that.

All Fours (novel by Miranda July)

Miranda July is one of those people with an unfair, jealousy-inducing level of talent—she’s a great filmmaker, an amazing writer, a good dancer, and she’s attractive. Plus she has a cool name1. I was hesitant to include All Fours on this list because everyone has already heard about it and there’s really no need for me to add to the chorus of voices saying that it’s very good, but whatever, it really is very good.

Bible App (subway ad)

I don’t know if this counts as something I “read,” exactly, but this Bible app ad I saw on the subway is a master class in concise copywriting:

That’s it for this year! If you liked this, I made similar lists in 2021, 2020, and all the way back in 2016. I also review the books I read on my Goodreads, though those are mostly just intended as notes to myself. Give the heart button below a tap if you enjoyed this; if you hated it, forward it to ten friends with angry commentary.